Learning to Talk to Whales Using AI

How artificial intelliegence is breaking the species language barrier

How artificial intelliegence is breaking the species language barrier

You may or may not have heard of SETI. The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Life (i.e. aliens) has had waves of attention coinciding with the bursts of popularity aliens have enjoyed in the media, and events like the detection of Oumuamua. But even if you have heard of them, you probably haven’t heard of their actually way cooler whale division, Whale-SETI, which deserves so much more attention than it currently gets. Basically, they’re trying to talk to whales, and recently had the longest conversation with a whale so far.

The interaction was started by playing a pre-recorded contact call from a boat in south-east Alaska, and after three attempts, a 38 year old female humpback whale called Twain approached the boat and began to reply. The team continued playing the contact call over 20 minutes (the maximum time allowed by the team’s research permit), and Twain responded 33 times over that period, occasionally pausing to go to the surface and breathe. The contact calls were varied to match Twain’s timing, and she adjusted her own vocalisations in response.

A photograph of Twain’s fluke (the end of a whale’s tail), taken by the Whale-SETI group (NMFS Permit #19703)

A photograph of Twain’s fluke (the end of a whale’s tail), taken by the Whale-SETI group (NMFS Permit #19703)

Observers who couldn’t hear the conversation itself identified three behavioural phases in the conversation: engagement, agitation and disengagement. These coincided with changes in both the latency of Twain’s responses, and her level of adjustment to the team’s varying contact calls. The agitation phase, for example, was characterized by what the research team described as ‘wheezy or reverse forced surface blows’, which appear to be indicative of excitement or agitation (Thompson, Cummings & Ha, 1986; Watkins, 1977). Meanwhile, the disengagement phase began when Twain began moving away from the research vessel following two more typical blows.

Ultimately, it wasn’t the most complex conversation; they basically just said ‘hi’ backwards and forwards for a while, but it demonstrates a foundational understanding of whale communication, our ability to engage them in a conversation (however simplistic), and our ability to broadcast whale sounds in a way that appears to be understandable to humpback whales. It should be highlighted that the broadcasted calls were recorded from a group of humpback whales the previous day, in which Twain was present. This choice of signal and its familiarity to Twain may very well be tied to its salience to her, and her resulting engagement. Raw footage of the interaction can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHCBJ1rWfqQ.

The Glacier Seal – the vessel used by the Whale-SETI group for their communication with Twain (NMFS Permit #19703).

The Glacier Seal – the vessel used by the Whale-SETI group for their communication with Twain (NMFS Permit #19703).

But as exciting as this was, the confusingly similarly named Project CETI may be even closer to fully understanding whales, having published several papers regarding hypothesised whale linguistic systems and machine learning techniques for translating their speech. And while Whale-SETI is using whales as a proxy for developing alien communication methods (which is silly, because talking to whales is way more exciting), CETI has understanding cetacean languages as their chief end goal. They recently analysed over a decade of sperm whale ‘speech’ data in collaboration with MIT’s Computer Science & Artificial Intelligence Laboratory using artificial intelligence.

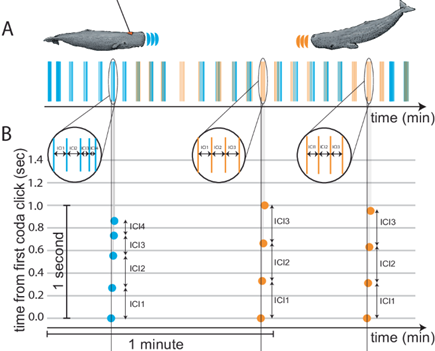

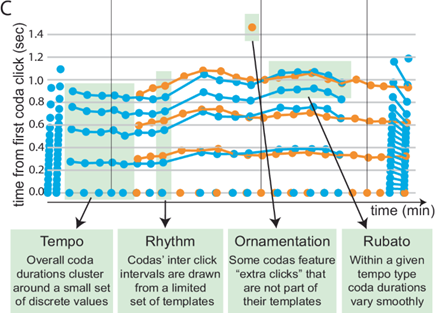

The results, published in Nature Communications, dissect the tempo (overall speed), rhythm, ornamentation (embellishment) and rubato (length variation or rate of delivery) of the whale’s communication. See the diagram below from their article for more clarity on these terms:

Figure 1 - A two minute exchange between whales, broken down by time-time plot B (illustrating the time in exchange of a click, and its duration), and a second time-time plot, A (visualising the connections between matching clicks in adjacent phrases). Source: Sharma, P., Gero, S., Payne, R. et al. Contextual and combinatorial structure in sperm whale vocalisations. Nat Commun 15, 3617 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47221-8.

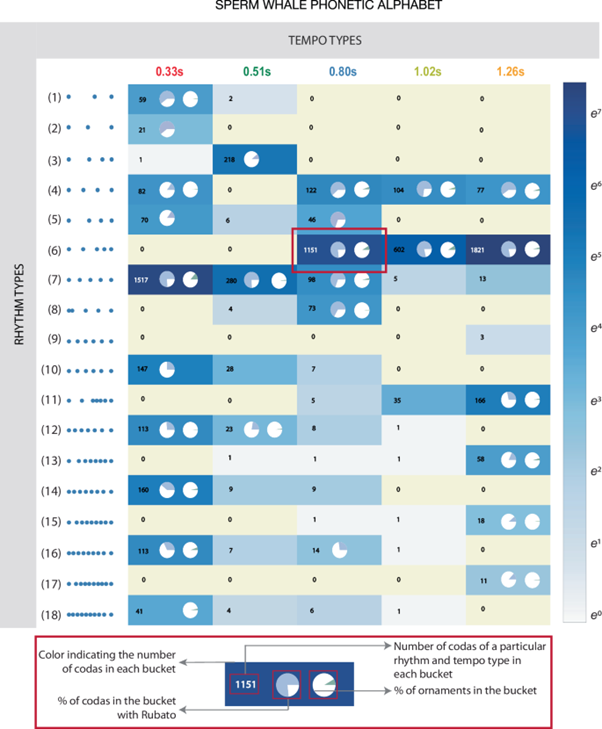

This research led to a proposed phonetic alphabet, describing the underlying building block sounds used by sperm whales to create words and phrases. These phrases, or codas, consist of 3-40 clicks, with varying tempo, rubato and rhythm, with additional ornamentation used to embellish the communication. Rhythm and tempo appear to be context-independent, and likely serve to distinguish fundamental ‘words’ or ‘phrases’, while rubato and ornamentation were found to be context-sensitive; potentially adding further meaning and tone.

Data was captured using acoustic tags attached to whales, called ‘D-tags’, which are non-invasive detectors with a variety of sensors, attached using silicon suction cups modelled on suckerfish, and released automatically when recording completes (with built-in beacons for recovery). Machine learning and various statistical analyses were then used to identify and cluster recurring linguistic features of whale communication, and make predictions about what codas might come next, and ultimately producing a sperm whale phonetic alphabet:

Figure 2 – Sperm Whale Phonetic Alphabet. Source: Sharma, P., Gero, S., Payne, R. et al. Contextual and combinatorial structure in sperm whale vocalisations. Nat Commun 15, 3617 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47221-8.

This alphabet can be considered a parallel to the various sounds humans can make, which from our own phonetic repertoire. Although, as with humans, not all combinations or sounds necessarily make an appearance in language, and many aren’t found in the dataset that was analysed.

In terms of the specific techniques used, these were largely statistical, with Spearman’s Rank used to evaluate correlation in duration changes across coda triples (providing a method to assess if changes in rubato (temporal variation) are correlated over time), and Fisher’s Exact test used to identify any non-random associations between categorical variables (e.g. the appearance of ornamentation at the beginning or end of call sequences, and changes in chorusing behaviour following ornamented codas). However, automated clustering (for categorising codas into rhythm and tempo groups) and pattern recognition in time-series data (e.g. detecting patterns of rubato across codas) were likely conducted using machine learning algorithms. I’ve contacted the authors and haven’t heard back yet, but for the former, something like DBSCAN or hierarchical clustering was likely used.

These algorithms allow unlabelled data (i.e. data that hasn’t already been assigned a group or category) to be group together in ‘clusters’ based on similarity. They operate by evaluating the distances or similarities between data points and grouping them into clusters, such that data points in the same cluster are more similar to each other than to those in other clusters. This method is particularly useful for exploratory data analysis, pattern recognition, and feature extraction, where the groups the data might be broken down into are unknown. Think trying to sort some tableware into sets, without knowing anything about it. It might turn out to be all plates, but of different colours, in which case the algorithm would group them based on matching colours. Or everything might be the same colour, but a mixture of plates, bowls and cups, in which case a clustering algorithm could group them based on these categories. With traditional supervised learning, each of the possible categories would have to be known before hand, and a model would be trained on examples of each to recognise them, so it could sort new examples. However, if the categories are unknown beforehand, this becomes impossible, and a clustering algorithm can be used instead to identify points of similarity and group using these. In the case of this study, clustering was used to group codas into rhythm and tempo types, and allowed the researchers to identify a recurring phonetic alphabet.

The DBSCAN clustering algorithm (or Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is particularly useful for data with noise, where clusters aren’t similar size. It groups closely packed points and marks datapoints in low density regions as outliers (i.e. background noise). Hierarchical clustering, on the other hand, builds a tree of clusters (with each smaller one then clustered into increasingly bigger ones), and is beneficial when a natural hierarchy could exist (e.g. finer versus broader rhythmic distinctions).

Time-series data, on the other hand, needs to be analysed with an algorithm that preserves the ordering of the data. For example, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) process once section of data at a time, and use the output of that as an additional input when processing the next section of data. This allows them to maintain the context and ordering of data in a sequence, like whale speech. Another option would be a transformer model, which is the architecture used in large language models like ChatGPT, and similarly preserves context and ordering.

Beyond this study, CETI has combined their D-tags for recording audio with drone footage of whales near the surface, to produce videos of whales interacting with their synced-up conversations. Because of how well the tags stay attached, even during deep dives, researchers have watched as whales go silent while hunting, and return to normal conversation once they return to the surface. AI has been used to separate the voices of different whales, and insights include the whales taking turns to speak, just like humans do, and identifying the whale ‘word’ used to initiate a dive. Two to four years from now, the data collected by CETI is expected to include over 4 billion recordings, and with AI rapidly advancing, it may not be long before we’re able to converse with whales as easily as each other.

For example, a studied published in February 2024 managed to train an AI model to understand language in a similar way to how we would teach children, by providing a video feed from the child’s perspective to provide context for speech it heard, and allowing the model to slowly pick up words and grammar. This ‘contrastive learning’ allows an AI model to learn to associate elements of two streams of data; in this case visual and linguistic information. Following the training, the model was able to correctly pick previously unseen images to match words it had learned, showing the feasibility of this methodology. It’s not inconceivable that technique could be employed with whales, using an AI being ‘raised’ like a whale, with exposure to similar sensory inputs alongside language.

Regardless, the success of CETI’s research so far represents a dramatically growing understanding of whale speech, and a surprising symmetry with our own: although we should be wary not to assume that whale communication necessarily matches human preconceptions of language. There is also much to be said about the ethics surrounding this goal, and the AI technologies involved, and I highly recommend reading this really thought-provoking article by Tom Mustill: https://www.tommustill.com/afterword-to-how-to-speak-whale.

Sources:

https://peerj.com/articles/16349/

https://bmccowanlab.com/current-research/humpback-whale-research/

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240709-the-sperm-whale-phonetic-alphabet-revealed-by-ai

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-47221-8

https://news.mit.edu/2024/csail-ceti-explores-sperm-whale-alphabet-0507

https://www2.whoi.edu/site/marinemammalbehaviorlab/dtag/